If I ask junior doctors, and even more experienced consultants what they would consider their best investment, or what they would consider a safe investment, the almost invariable answer is property. Of course, that is after the more politically correct answers along the lines of, “My education,” or, “Marrying my current partner.” In the English-speaking world the desire to own where we live has reached almost pathological levels. Yet it is a pathology I share on an emotional level. I am attached to where I live: I chose to live in my house, my loved ones live there too, we have altered it to suit us, it has our stuff in it, and it has our memories. At the same time, it is also the single largest asset I currently have, although I am working on changing that. Many consultants, when they settle into their new job, work out how large a mortgage they can afford, and then indebt themselves to the hilt. Lenders are happy to take then on, as they have good prospects for continuing employment and rising salary for a good few years.

In coffee room conversations, those with the largest mortgages will then go on to say that their house is their pension. There are problems with this strategy. Emotional attachment and investment rarely go well together, so what if you like the house so much that you do not want to move out when you get older? What if the kids beg you to keep the house they grew up in, as they love coming back for Christmas? What if the kids don’t leave home on cue, or keep returning? What if by the time you have allowed for selling costs, removal expenses, and the fact that the perfect retirement property happens to be more expensive than you thought, that you don’t have as much left over as you thought you would, and what if, when you want to downsize, it takes a year or more to shift your house in a stagnant market? Of course, you could sell it quicker if you cut the price, but then your plans are scuppered. Finally, what if it is not such a great investment after all. Despite the evidence of the last few decades, there is no fundamental law of nature that property prices always rise.

Property prices do not always go up……….

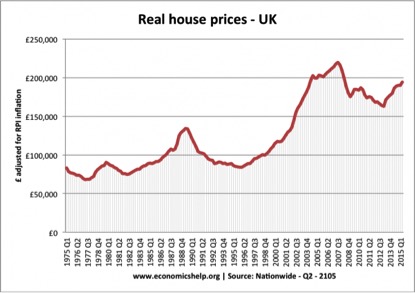

You probably have trouble believing that statement, and chances are, so will your parents. Apart from some brief dips in property values in the late 80s, mid 90s, and with the American housing loans initiated crisis of 2008 onwards, prices in the UK have risen with respect to inflation (the only important measure) for the last 50 years, or even longer, viz.

Fig 1. UK house prices adjusted for inflation over a 40 year period from 1975 to 2015. Superficially, highly reassuring for the “house process always rise” argument. But what if you bought in 1988 and sold in 1995? Or 2007 and sold in 2013?

So the greatest proportionate drop in the last 31 years is about one third over about a five-year period from 1988 to 1993, and things looked a bit rocky after the multiple assaults on the world financial system from 2007-8 onwards. Nonetheless, over a lifetime (or 25 year mortgage period), it looks fairly reassuring. Another reassuring feature of property as investment can be seen when comparing the graph below with the one above.

Fig 2. Raw increase in house prices across the UK on a per year basis. This graph of year on year house price changes is much spikier than figure 1 might lead you to expect.

You can see that in the 1970s, some years could see 30 to 40% increases in house price. But look at the inflation corrected graph in figure 1, and the rises are much smaller, or even non-existent over those same periods. So the sharpest spikes in house prices gains are largely down to inflation. At least in those periods, house prices broadly kept up with inflation. So this presents us with a general rule that could serve us well in an investment lifetime: since inflation is the reduced ability of currency to buy a certain amount of stuff over time, then stuff, by becoming more expensive, can be a preserver of wealth, and is better than money in the bank in inflationary times

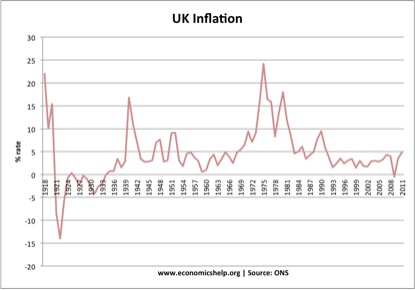

If you are under 25, you have been born into the low inflationary period at the right hand end of the graph below.

Fig 3: UK inflation from 1918 to 2011.

It would be unwise to presume the present, generally less than 5% inflation (while the Bank of England aims for 2%) will persist. Everyone hopes it will, but reality has a way of intruding. What if you had lived in a high interest, high inflation period? When inflation is running high, first government, and latterly the Bank of England, set interest rates higher to bring down the ability and willingness of the population to purchase things. Look at the blip above in the late 1980s to early 1990s in inflation. What happened then? Bank interest rates rose to over 14%, and house prices accordingly lowered. Many got stuck with negative equity with a house worth less than a mortgage that they could no longer afford to pay. Suppose in the future rates rose to 10% with a mortgage of £200,000. Just to keep up with interest payments you would need £20,000 of after tax income each year. Such a rate rise is unlikely, but not impossible. The long low period of 0.25 to 0.5% is unprecedented, and abnormal.

Fig 4. Credit Suisse report on global house prices

accessed August 4th 2019)

Lest we begin to think that property is guaranteed preserver of wealth over all longer time periods, lets examine the lessons of the graph above. Adjusted for inflation, the earlier part of the 20th Century was a pretty dire time in which to make your house an investment. If you had bought a house in the UK at the turn of 1900, you would have had to have waited until the end of the Second World War before you got our money back, and the situation for France and Norway is even more dispiriting. But had you lived in such days, you would have had many other issues to concern you. Some things are more important than money.

So, in conclusion, enjoy where you live, ask if you could still pay the mortgage if interest rates doubled (or as they are now at historic lows, quadrupled!), and do not assume, in that Anglo-Saxon way, that because you have masses of money locked up in a house that you are rich. Home is important, so you don’t want to have to sell it to raise money. There are other ways to create financial comfort, as I hope future blogs will make clear.

Declararion of interest: we own our own home and are fortunate enough to have no mortgage, having lived through a time of rising house prices in real terms. I have no immediate plans to sell, so a plummet in house prices might benefit those wanting to get on the housing ladder and do me no real harm.